Brickshistory.com is part of the brickwahl.com universe that also includes brickspicks.com (music and culture), bricksbrain.com (cognition, perception and my epilepsy), brickspolitics.com and bricksscience.com.

Cylinder seal

(2022)

A lovely tool for a long vanished Mesopotamian technology, to impress cuneiform signatures onto clay cylinder seals, typically to authenticate legal documents such as contracts, receipts (as in a receipt for a shipment), deeds, wills and like that. Which is how far back paperwork goes, to the dawn of civilization. Except that it wasn’t paper yet. It was clay tablets, at the beginning, baked hard and stored in archives (which also go back to the dawn of civilization) and surviving thousands of years. Upwards of a couple million of such documents have been found, mostly perfectly dull receipts and the like, and there might be millions of such documents still buried in the sands of Mesopotamia. This is what writing was invented for, not story telling or poetry. Before literature was ever even imagined there were a couple thousand years of receipts, and pretty baubles like this to sign them with.

From Archaeohistories on Twitter:

Gold Ring with Cuneiform Inscriptions, found from Uruk (3500 BC).

Cylinder seals were invented 3500 BC, in the Near East at contemporary site of Susa in southwestern Iran, and at the early site of Uruk in Southern Mesopotamia. They were used as an administrative tool, jewelry or magical amulet.

The seal itself was usually made of hard stone, glass or ceramics such as Egyptian faience. As the alluvial country of Mesopotamia lacks good stone for carving, the stones for early seals were probably imported from Iran.

British Museum

At Franklin and Vine in the 1890s

Franklin and Vine, 1890s, just a couple blocks north of Hollywood and Vine. Hollywood Blvd—then called Prospect Avenue, a graded dirt road—was already there, but nothing else made it past the 1920s, when Hollywood’s Arcadian past disappeared under studio lots and pavement. This view looking south was all city in a generation or two, the last of the bean fields a couple miles on past Melrose went under the bulldozer in the 1930s. You walk these streets now—well, drive these streets, no one walks here—and you can’t imagine it was all farmland as far as you could see.

Disguised Hitler

It wasn’t assumed at the time that Hitler really would stay in Berlin and kill himself and the Army distributed photos of a disguised Hitler among US troops in case he tried to pass himself off as someone else. Sounds crazy now, but Heinrich Himmler, perhaps the second most powerful figure in the Third Reich, actually did disguise himself as a sergeant and managed to avoid capture for three weeks. But Hitler kept his word, and blew out his brains in the Fuhrerbunker in the center of Berlin when the Russians were three hundred meters away. Thus ended the thousand year Reich. For decades, though, rumors persisted that Hitler had escaped. The jokes lasted even longer, though by the 1980’s Hitler would have been reaching the century mark and the rumors and jokes finally faded.

But in 1945, here’s what the Army thought a disguised Hitler might have looked at. Take your pick. Hitler’s double, by the way, who did look like a disguised Hitler, and was down there in the Fuhrerbunker with the real Hitler until the final days, was executed by the SS not long before they executed Hitler’s dogs. Imagine his surprise. I’ve never understood why he stayed. He could have snuck out, shaved the mustache, cut his hair, and escaped with the civilians still leaving Berlin even then. He could have written a memoir. Gone to Hollywood and imitated Hitler in a zillion movies. But he stayed. I almost feel sorry for the shmuck. Almost.

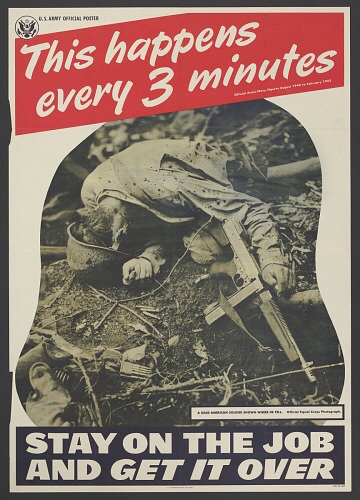

Every three minutes

An American WW2 poster. Not exactly a morale booster. Since the war hadn’t been brought home—no bombing of American cities, no battling armies in front yards—it seems like the Army’s War Information Office figured the public needed to be reminded that their sons, husbands, brothers and sweethearts were still getting killed with regularity. I suspect this is from 1944, probably later in the year, when the rapid advance across the plains of France bogged down in nasty fighting with desperate and fanatical Germans in the wooded hill country on the German border. Ugly stuff you never hear about anymore, and the dead piled up in neat statistical averages of twenty an hour and telegrams went out to homes four hundred and eighty times a day and the Army figured people needed to be reminded of that. The war wasn’t over yet.

(Though a pal suggests that this was not intended for the public but for the Army, for personnel not in combat units, which would’ve been most of them. Good point.)

Moche

From Archeology & Art on Twitter, a necklace of gold and glass beads (for the toads’ eyes) from the Moche civilization of Peru. Unknown date except that the Moche clung to a narrow stretch of the Pacific coast in what is now northern Peru and for a brilliant six or so centuries existed from about AD 100 to 700, so this was made sometime in there. We can only guess at their demise. A thirty year super El Niño followed by a thirty year drought doubtless brought them to the brink, and then archeological evidence of civil war and—perhaps the final blow—attacks from the Huari civilization to the east (one of the succession of pre-Incan civilizations in the Peruvian highlands) seems to precede their final disappearance. Beyond the archeological evidence and supposition, though, little remains to us, such being the fate of non-literate civilizations. Instead all we can do is look at their extraordinary artwork, like these lovely little golden frogs, and wonder about the people who made them.

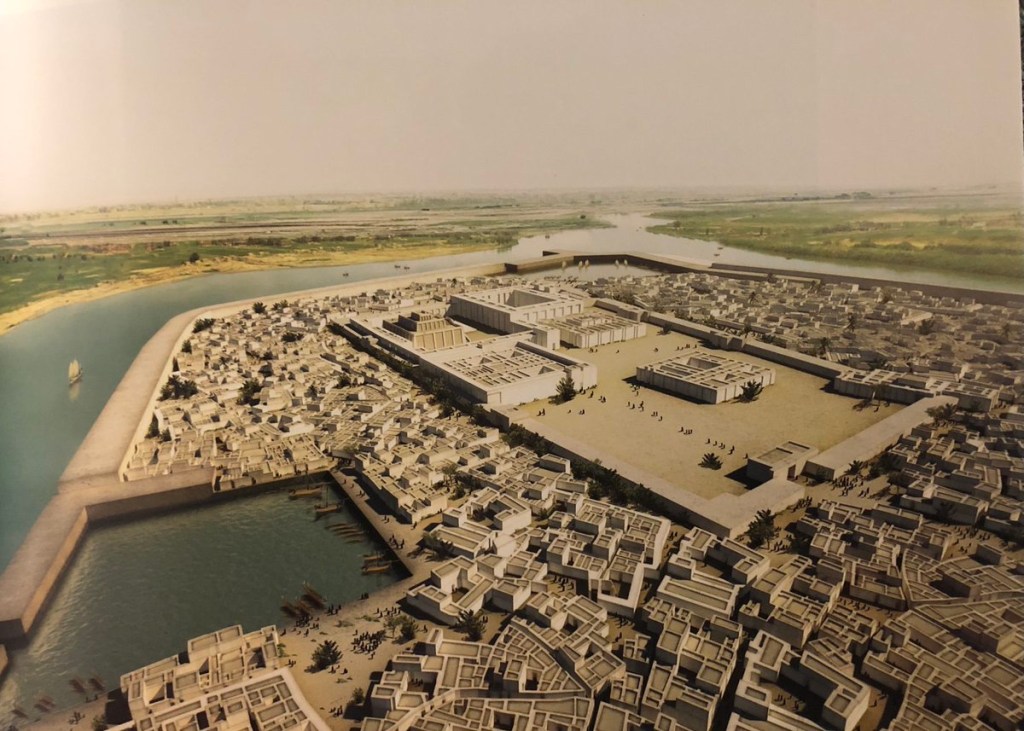

Ur

Here’s a virtual reconstruction of the city of Ur around 2500 BC or so, or upwards of five thousand years ago. This is based on the remarkably well preserved mud brick structures (due in part to the dry climate, and in part to the excellence of the construction), which gives a blue print of the city in exceptional detail. There is also an enormous quantity of documents—mud tablets baked hard by the sun and in ovens—written in cuneiform which give insight into almost every aspect of life, politics, war and commerce in the city’s 3,300 year history (which coincides neatly with the history of cuneiform, actually, the first cuneiform preceding the founding of the city by only a couple centuries.) Ur was perhaps the very first city, and certainly the very first great city in the modern sense. Take us back in time and put us atop the ziggurat that towers over it and we would take in the view and know we were looking at a city. The way the Chicago skyline seems to rise out of the fields a great distance away was how Ur’s towering ziggurat would have appeared to rise from the plains of Mesopotamia to a Sumerian farmhand. Ur was the model that most cities from Europe to Central and South Asia to the northern half of Africa followed, even though most never knew it. It became the ur meme, the fundamental urban design concept, like how an alphabet invented in the Sinai by a handful of literate turquoise miners became the conceptual model for nearly all the world’s alphabets thereafter. Thus was the urban design deliberately laid out by the planners of Ur over five thousand years ago imprinted upon civilization. Only cities in the Far East and the Americas and sub-Saharan Africa were founded and conceptualized independently. It was in Ur where humans first figured out how to create an urban civilization. Crime, epidemic disease, slums, crowding, pollution, repression and extremes of wealth and poverty followed the idea as it spread, sure, but so did the glamour, excitement, inspiration and thrill of life in the big city, which is why so many of us live in one five millennia later. Ur itself, though, was abandoned about twenty seven hundred years ago, forgotten, it’s bones covered with blowing sand and dust till all that remained was a few odd hillocks, as if it never were.

(Unfortunately I don’t know the source of the digital image.)

Ordinary Roman footwear

Shoe of an ordinary Roman soldier, a legionary, discovered while excavating a Roman fort in Germany. These were just workday shoes, perhaps not worn on campaign but certainly when tooling around the camp in the long months between. Just ordinary Roman footwear. The workmanship and detail look like something you’d pick up at Target today. It’s so easy to underestimate the day to day sophistication of Roman civilization, which makes the plunge into several centuries of the Dark Ages all the more stunning. The Roman Empire in the west, the part ruled from Rome, was swept away in the space of a century (the empire in the east, ruled from Constantinople, hung on another thousand years, till 1453), and with it disappeared so many skills, from running water sewage systems to the cobbling of comfortable shoes, and it took nearly a thousand years to remember how to do it again. Now, two thousand years later, we can make shoes just like this, and out of plastic, and in a riot of colors. And if that ain’t progress, I don’t know what is.

A pair of dice

Here’s a technology that hasn’t changed much in at least 4000 years. The Indus Civilization was astonishing, with beautifully laid out cities, running water and waste drainage systems and a complex economy, alas, we can’t seem to crack the writing, so what we know is mostly deduction. In neighboring Mesopotamia archeologists have dug up a half million cuneiform tablets (baked in an oven they lasted a long time, and if the palace they were stored in was burned down when the city fell, they become hard as rock) and it’s guesstimated there could be a million more still in the ground, so we know incredible amounts of information about Sumerians, Babylonians, Assyrians, the nearby Hittites and, all the other peoples who recorded their thoughts, commands, gossip, prayers, transactions, histories, whatever. And what we do know of the games the mysterious Indus Civilization people were playing with these dice we might know from some Sumerian trader—probably complaining in a cuneiform tablet about being cleaned out by some Indian hustler with a pair of dice.

Unguentarium

From archaeologist Dr. Nina Willburger on Twitter about this two thousand year old unguentarium and also a great excuse to write unguentarium three times, and I’d never even heard of an unguentarium before. “This delicate Roman blue and white marbled glass unguentarium,” the good doctor begins, “a vessel to hold oil/perfume, was made from translucent dark blue glass with trails in opaque white, dating 1st century AD.” Almost telegraphically terse, but she nails it. Let your eyes loll over the picture, it’s such a beautiful thing. Romans were absolutely masters of glassware, and they mass produced the stuff, glass blowers huffing and puffing all day long creating things like this. Theirs was was the world created by Caesar Augustus and his Antonine Dynasty, the very apogee of Rome, the world of I Claudius, the Antonines and the three emperors of the Flavian Dynasty who filled out the rest of that glorious century. Those were the years you probably visualize when you think of the Roman Empire, when delicate things like this could be found from Scotland to Mesopotamia and traded far beyond, and sometimes, somehow, they survived the two thousand years since, and we can gaze upon them, looking as if they were blown from molten glass only yesterday.

Pershing Square, 1944

There probably wasn’t much to do in L. A. on a warm day in early June of 1944 if you were a senior citizen, there were only so many night watchmen gigs and air raid wardens were no longer in demand. And it certainly wouldn’t have been easy to get around, not with rationing and the buses and trains and red cars packed with younger people coming and going to work—all the plants ran three shifts, 24/7–so the benches are packed downtown in Pershing Square. The headlines are screaming about the Invasion just unleashed on the beaches of Normandy, which is certainly what these gentlemen are all talking about thinking about and worrying about, and reminiscing about how it was back in ‘17 when it was their turn over there. They’re talking about the war, this war and theirs, and their telling tales of their youth, some even true, and they’re talking about their aches and pains. Meanwhile the War gets won without them.