I think when English and Americans condemn France for its collaboration in World War 2–and I am not justifying the craven Vichy government–they forget one key point about themselves. And that is that unlike Britain and the USA, France was conquered, occupied, and then left in part a puppet state, a succession of events which they had no control over once the Germans had flanked their armies and left Paris, and France itself, essentially defenseless. A simple miscalculation by the French high command–they had placed the left wing of their army, with most of their armored forces, too far forward to respond to the German blitz through the Ardennes–brought about military collapse. It was sudden and complete, even more sudden and complete than the defeat in 1871, and completely opposite the brutal slog of 1914-18. War like this didn’t even seem possible. The French–the government, the press, the labor leaders, the armed forces, the population–were stunned into cowed acquiescence. Cleverly, their Nazi conquerors offered employment and a future to all kinds of French citizens. The French were now subjects with a stake in the future of the Third Reich, a status not granted to the citizens of Poland, etc., who faced extermination by murder or starvation or endless chattel slavery.

The German occupation was helped along immeasurably by the presence of a very large pre-war fascist and extreme rightist movement in France. This was true across large parts of Europe (even the neutral Swiss arrested their own Nazi sympathizers just in case). These homegrown fascists were more than willing to take up leadership, administrative and policing roles in both Vichy France and German occupied France, as well as throughout the French colonial empire. It’s hard not to think of these French collaborators with a visceral disgust, even seventy five years later. Yet we’ve almost forgotten that there were fascist elements–and Stalinist elements–in Britain as well ready to take their place in their own Nazi occupation government should it come to be. Had Hitler’s planned Operation Sea Lion somehow succeeded in crossing the English Channel there can be little doubt that the virtually disarmed Britain (with nearly all the Royal Army’s equipment–cannon, tanks, machine guns, etc.–abandoned at Dunkirk) would have been conquered as easily as France. And that there would have been some degree of collaboration with Nazi occupation authorities in England (remember the film It Happened Here?) Would there have been the same degree of collaboration as in France? Hard to tell. The fascist movement was smaller in England, but it was not insignificant. Indeed, it included the former King Edward, then living in France as the Duke of Windsor, and who was quite chummy with Adolf Hitler as late as 1939. (The Nazis had big plans for Edward, but the British spirited him away to the Bahamas before the panzers reached him.) In France the suddenness of defeat made fascism seem irresistible, inevitable. It’s hard to see why England would have reacted any differently. And it’s not like the English would have had much choice. To refuse to collaborate was often the last decision one ever made.

For argument’s sake, and strictly theoretically speaking, let’s also assume that had Britain or France somehow been occupied by the Soviet Union, as were the Baltic States and eastern Poland in 1939, there would have been no shortage of collaborators either. The NKVD (Stalin’s vast secret police organization) had no problem finding local Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians to work for the Soviet occupation–even as the same NKVD was arresting, torturing, imprisoning, exiling or executing hundreds of thousands of the collaborators’ countrymen. Hitler or Stalin, it did not matter, there were quite literally millions of civilians, police and military the breadth of occupied Europe willing to join up (there were half a million “Germanic non-Germans” in the Waffen SS alone, though many of those were conscripts, and perhaps a million Russians assisted the Wehrmacht as soldiers or auxiliaries, if only to avoid starvation as prisoners of war). Had the US somehow been conquered by Hitler or Stalin there would have been no shortage of collaborators here either. It might seem immoral, ludicrous and inconceivable now, but in the 1930’s both fascism and Stalinist communism were seen as legitimate ideologies by a remarkable number of people. That became clear when the Spanish Civil War erupted and the intelligentsia and artistic communities across the western world began splitting into two camps. I am not sure now which side had more supporters, even in the U.S. In Hollywood there were rallies and star studded fundraisers on behalf of the fascists. Though it wasn’t so much fascism that drew these people, but anti-communism. By this point communism–then still more widely known as bolshevism–had terrified many. Remember that this was during Stalin’s purges and show trials, and after the appallingly brutal famine in the Ukraine (the Holodomor.) Bolshevism was not revolution like our own genteel (or so we remember it) American Revolution. This was a French Revolution gone utterly mad and evil. Thus Franco, wrapping himself in the anti-communist banner, received a surprising amount of support even among western intellectuals and bohemians, far more than we care to remember now. I mean Gertrude Stein? J.R.R. Tolkien?

On the other hand, the Spanish Republic’s supporters splintered immediately into liberals and socialists on the one hand and an ardent Stalinist bloc that in Spain actually purged the non-Stalinist Republicans, executing hundreds, sometimes right in the front lines. Stalin’s paranoia had an incredibly long reach. It is forgotten now that George Orwell himself, the voice in English of the anti-fascist Republican cause, barely escaped such an execution in Barcelona. Agents came to his hotel looking for he and his wife. They escaped to France, but just barely. (The film Land and Freedom vividly shows some of this madness.) Fascism, on the other hand, had an almost universal solidarity, it was a mailed fist. Meanwhile, and tragically, anti-fascism was splintering into every faction imaginable, and the hard line Stalinists saw everyone else on the left as an enemy to be subverted or destroyed before Stalin got around to defeating fascism. (In fact, Stalin’s plans to launch a surprise assault on Nazi Germany were sidelined by his decision to purge, torture and execute nearly all his generals instead.) Spain became a microcosm of what the rest of Europe would be in the 1940’s, with Nazis and locals willing to serve them, and Stalin’s agents and those willing to serve them. Somehow, though, both Hitler and Stalin failed to make permanent inroads in Spain. Although a division of Spanish volunteers served on the Russian Front–and after Franco withdrew them, a core of 3000 Spanish fascist fanatics refused to leave, fighting till the war’s end– Franco retained his independence and his nation’s neutrality, and the Spanish communists, once Franco was gone, became genuine democratic socialists. Unfortunately you can’t say the same for the rest of Europe. Fascism was ended only by Germany’s military defeat, otherwise it might still in charge now. And Stalinism–though somewhat mellowed with age– fell only when the Soviet Union imploded through economic failure. Neither showed any sign of ever going away on its own. There was a limitless supply of people in every occupied state willing to do their German or Russian master’s bidding, even if it meant shooting down their own kind in cold blood.

It’s as if the raw material of collaboration was there throughout the Western world just waiting for its moment. My father remembered being taken to beer halls when he was a boy by his father. The rooms were draped with Nazi flags and people listened to Hitler’s speeches on the shortwave and cheered lustily–and this was in Detroit, Michigan in 1940. In Europe of course it was far worse. Switzerland had to arrest politicians and military men who actively supported Hitler (though the head of the Nazi Party in Switzerland was assassinated by a Croatian Jew in Davos in 1936 in a rare and prescient act of resistance), while both Hungary and Romania were spared conquest by the Nazis because homegrown fascist movements had taken over the government. The cost of the more honorable alternative of resisting the Third Reich was all too vividly shown by Yugoslavia, which suffered through four years of appalling warfare and murderous oppression that killed nearly ten per cent of the pre-war population.

Collaboration made far too much sense for most people at the time. It would today as well. The Polish resistance–the Home Army–was 400,000 strong in 1944. The French resistance (before the Allies landed) had one quarter of that. France had a larger population than Poland and had one twelfth of the civilian losses of Poland. But the Germans had forbad Polish collaboration. The Poles were left with no alternative but resistance. If they were caught they were almost invariably killed, but they were going to starve or be worked to death anyway. But the French could choose to collaborate actively (by assisting the regime) or passively (by not assisting the resistance). In not resisting you would survive, perhaps even thrive. Your family would eat. Joining the resistance meant a strong likelihood of torture and/or death, perhaps extended to your family members and friends and neighbors. So most passively collaborated. It was the logical choice, collaboration. They had to think about their families. I am not being sarcastic here. Passive collaboration was the genuine logical choice for most Frenchmen. In terms of taking care of their own, it was the correct thing to do.

Unlike Britain, the USA or Switzerland, France had the misfortune to be conquered, and then the fortune to be handled fairly lightly by the Reich. The Danes, good Aryans that they were even if they despised the Germans, were occupied with even a lighter touch (while spiriting almost 100% of their Jews into Sweden and out of the reach of the Holocaust), but the French (the non-Jewish French, anyway) still did extremely well compared with the genocide against the Slavic Poles. It was the relatively mellow German occupation in France made collaboration possible. Even had a Polish fascist (and there were plenty of them pre-war) wanted to join the Nazis as so many French citizens did after the surrender in May of 1940, he wouldn’t have been accepted. (Recall Sophie’s Choice where Sophie’s father was a Polish fascist, yet she still was sent to a death camp.) Besides, the Nazis went through and slaughtered the Polish intelligentsia early in the occupation, thus in one stroke sparing Poland discussions like those about French collaborationist guilt. (As for their guilt in the Holocaust, that is another matter). But any Célines there may have been in the literary salons of Warsaw were quickly executed by the Nazi occupation authorities along side the patriots.

We can condemn the French–and all the other nationalities too–for collaborating. And we should. But we should also keep in mind that our own compatriots would have acted no better in the same circumstances. With a breath of fascism in the breeze today, it’ll be interesting to watch how people collaborate these next couple months of 2016 in the United States. We will be surprised, I suspect, at who switches sides, and how fast, and without blinking an eye.

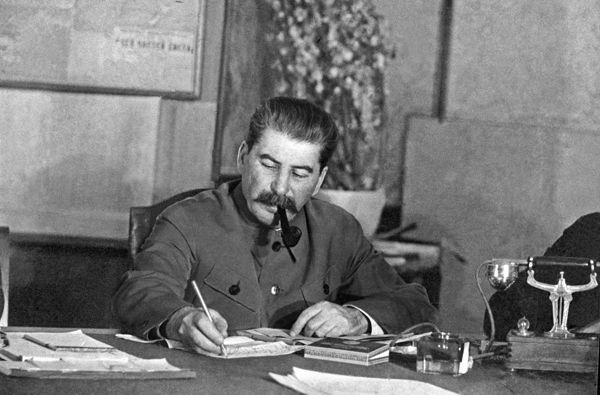

A member of the French Milice (the Vichy military police) guarding captured (or arrested) members of the French resistance, June 21, 1944. Note the Hitler mustache….